KcurseK

Jared didn’t know the ship’s name. Only that it groaned like a grave when he stepped aboard. Anchored in Suisun Bay, part of the Navy’s ghost fleet near Benicia, California, the vessel had been dormant for decades. One of many warships left to rust in still water, stripped of duty but not of memory. Jared’s assignment was simple: inventory old storage spaces and lockers, and catalog what remained. But deep in the hollow guts of the ship, beneath rusted decks and layers of forgotten time, he found something no checklist could explain. And something inside him would never quite return.

In one compartment, Jared found an old, moldy canvas satchel at the bottom of a dented footlocker. No one had touched that locker in decades. Maybe not since World War II. Inside the satchel was a curious pocket knife. Black. Thin. Handle like folded armor. A leaping cat stretched across the grip, frozen mid-pounce. Below it, the letters K55K, the second K turned backward, like it was looking over its shoulder.

The backward K was deliberate. It looked back, always. On the person holding it. On the last life it took.

Jared didn’t know why he kept the knife. He was only there to catalog old storage spaces, not dig through ghosts. But the thing felt familiar. Like it recognized him. Like it had been waiting.

That night, back at the barracks, Jared placed the knife beside his keys and wallet on the table near his bunk. A simple thing. Nothing more.

He woke at 3:17 a.m. to the sound of metal, a single, sharp snap that echoed in the stillness of the barracks.

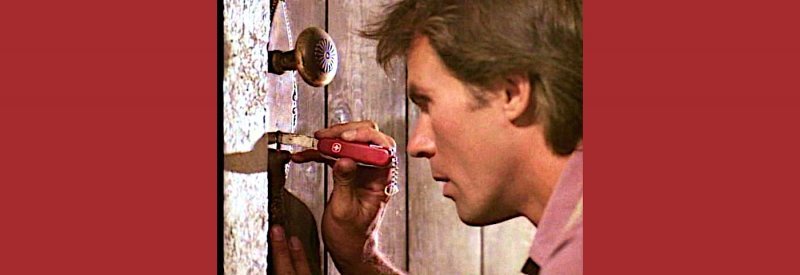

Jared sat up. The barracks were silent. The knife was open. He hadn’t touched it. He folded the blade closed and slid the knife into a drawer.

Over the next few nights, the knife kept finding its way out. Open. On his pillow. On the table. Once, in his boot. He suspected someone was playing tricks, but no one admitted it. Laughter turned into awkward silence.

Jared woke each morning with crescent-shaped wounds on his palm. It was as if something had curled up inside his hand while he slept, leaving its mark.

He stopped sleeping. Stopped talking. The others joked that isolation was getting to him. Too much time cataloging history in the hollow guts of dead ships.

He told the Chief, who just shrugged and muttered something about old gear sometimes carrying old energy. That was the Navy’s version of a ghost story.

Then people started disappearing.

First, the petty officer Jared had once accused of the prank. Jared had shown him the knife. Gone. No note. No trace. Next, a sailor on mid-watch, making his rounds while others slept. He passed Jared’s bunk and likely admired the knife. Vanished. Then a contractor Jared had let examine the knife. All touched the blade. All gone.

Jared tried to get rid of it. He threw the knife into the bay, the water black as ink, watching it sink into the dark, knowing it would return. That night, it was back. Sitting on the table. Blade open. Facing him.

Jared mailed it the next morning, wrapped in oilcloth. No return address. Just a note: It came back. I can’t keep it. Maybe you’ll understand.

He sent it to an address etched faintly inside the handle:

Hochstraße 55, Solingen, Germany. The factory no longer exists. It burned down.

But the package arrived.

No one signed for it. No one remembers who delivered it. The building was empty. Except for a single wooden table. With one thing on top. A black-handled knife. Blade open.

On a cold autumn morning in Berlin, the

Kaufmannstraße street market stirred as vendors opened their stalls under faded awnings. Among them, an old man named Emil sat on a folding stool. A relic himself. His table displayed one thing. A black-handled knife. A leaping cat carved into its side. Letters stamped beneath it: K55K. The second K backward, like something scratched it in with claws.

A young American named Daniel wandered the market. A tourist. Looking for something real. He picked up the knife, thumb resting on the leaping cat, tracing the backward K.

“You know what that is?” Emil asked in a crisp German accent.

“A Mercator,” Daniel said. “Lockback. Stainless. My grandfather had one. Brought it back from Europe after the war.”

Emil’s eyes twinkled. “Your grandfather. Army?”

“Navy,” Daniel said. “Chief Petty Officer. Said some Army guys traded chocolate and smokes for knives like this.”

“We traded everything,” Emil said. “Chocolate bought silence. Coffee bought time. But a good knife bought survival.”

Daniel turned the knife over. “Where’d you get it?”

“I didn’t,” Emil said. “It came back to me.”

He paused, eyes drifting to someplace far off. “My brother Otto carried one exactly like that. We weren’t soldiers. Not then. Just boys. But war didn’t care. Otto wasn’t brave. He was quiet. Smart. He didn’t carry the K55K to fight. Just to stay alive. He disappeared in 1945. I thought the knife was gone forever.”

“They say there was one knife like that in every war,” Emil murmured. “Just one. It didn’t fight. It watched.”

“And it found its way back?” Daniel asked.

“In 1991,” Emil said. “A sailor mailed it. Said it was found in a satchel aboard a U.S. Navy ship. Said he couldn’t keep it. No name. Just honor.”

Daniel opened his mouth to speak, but Emil placed the knife in his hand.

“Let it live another life,” the old man whispered.

Daniel nodded. Slipped the knife into his coat pocket. Walked off through the morning mist. That was the last anyone saw of him.

A week later, a street cleaner found the knife on the steps near the market. No blood. No body. Just the K55K. Gleaming in the moonlight.

The next morning, Emil was back on his stool. Same coat. Same table. Same knife.

Some say the cat on the handle is more than a logo. It’s a warning, cursed, soaked in the years, and sharpened by secrets. The knife doesn’t cut; it feeds. So go ahead. Look at the knife. Admire its shine. Let your finger trace the spine. And if you listen close, close enough to feel the edge press against the silence, you might hear it. Not a whisper. Not a cry. A purrrrr. Because when the blade opens it isn’t you holding the knife anymore. It’s the knife holding you.

So remember this tale the next time you’re tempted by a mysterious little blade in a flea market or a dead man’s drawer.

The knife should have taken Jared, but it didn’t, and that’s what makes it worse. It wanted him to watch.

The knife didn’t feed on Jared, because Jared was never the meal. He was the waiter. The offering. The witness. Every time he showed it to someone, handed it off, let someone else touch it, he opened a new door. A new vein.

Jared became its herald. Its courier. And it used him, not to kill him, but to break him.

And by the time Daniel took the knife, Jared was no longer stationed in Benicia. He was in a quiet wing of the base hospital, staring at the wall, not speaking, not sleeping, just mouthing the same four characters over and over, his lips moving like a prayer carved in rust:

K five five K

K five five K

K five five K

And the second K was always backward. Always.

Eine schwarze Katze, a black cat that is forever seeking its next herald.