You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

This is polio

- Thread starter mellowyellow

- Start date

dseag2

Dallas, TX

- Location

- Dallas, TX

I actually saw that both Neil Young and Joanie Mitchell, who withdrew from Spotify due to Joe Rogan's vaccine disinformation, had Polio when they were younger. That is most likely the reason they took such a hard stance against his anti-vaccination stance.

hollydolly

SF VIP

- Location

- London England

This is Polio....

...and this...

...and this...

hawkdon

Well-known Member

- Location

- Liberty MO

I do remember going to visit a relative who was in one

of those "iron lungs" when I was a small kidling....totaly

had forgotten about that...very sad.....

of those "iron lungs" when I was a small kidling....totaly

had forgotten about that...very sad.....

hollydolly

SF VIP

- Location

- London England

We had a kid in our school who'd had polio.. and had to wear iron braces on his legs attached to heavy boots.. to help him walk...I do remember going to visit a relative who was in one

of those "iron lungs" when I was a small kidling....totaly

had forgotten about that...very sad.....

terry123

Well-known Member

- Location

- Houston, Tx.

My BIL had it when young and before vaccine. He still has a limp when he walks. He is for all vaccines and very grateful to be alive.

Tommy

Senior Member

- Location

- New Hampshire

I had a friend in a similar condition during my early school days, Holly. Braces, boots, and he had to use crutches. Really nice kid.We had a kid in our school who'd had polio.. and had to wear iron braces on his legs attached to heavy boots.. to help him walk...

We lost touch after a few years but I ran into him again while working a summer job during college. He was working high steel. No braces, not even a noticeable limp.

I praise God for the miracles of modern medicine!

hollydolly

SF VIP

- Location

- London England

wow..I wonder if the boy in my school went onto be cured as well, I'd like to hope so...I had a friend in a similar condition during my early school days, Holly. Braces, boots, and he had to use crutches. Really nice kid.

We lost touch after a few years but I ran into him again while working a summer job during college. He was working high steel. No braces, not even a noticeable limp.

I praise God for the miracles of modern medicine!

Pappy

Living the Dream

I had a school mate that had this terrible disease in the fifties. It was our Covid scare at that time. Parents were scared to let their children go to school, go swimming and any gatherings. Scared the crap out of a lot of us.

hollydolly

SF VIP

- Location

- London England

this is what the kids looked like back in the 50's and 60's, who'd contracted polio...and before we all started getting vaccinatedI had a school mate that had this terrible disease in the fifties. It was our Covid scare at that time. Parents were scared to let their children go to school, go swimming and any gatherings. Scared the crap out of a lot of us.

Lewkat

Senior Member

- Location

- New Jersey, USA

When I was in nursing school we had to work for 6 weeks on a polio ward. I hated those "iron lungs." You could hear them breathing before you opened the door. Thankfully, we have more modern respirators today.

Incidentally, there was no polio vaccine available to us at that time. Only small children received those first doses. I never did get vaccinated, although my siblings did.

Incidentally, there was no polio vaccine available to us at that time. Only small children received those first doses. I never did get vaccinated, although my siblings did.

hollydolly

SF VIP

- Location

- London England

the vaccination was invented or first used the year I was born..'55 in the USA..and then in '56 in the UK...

Inspired by the desperate need to protect children from polio back in the 1950s, Duncan Guthrie laid the foundations for Action Medical Research. Now, we’re the UK’s leading charity funding vital research to save and change children’s lives and we’re forging ahead to fund research to help better understand the impact of COVID-19 on children.

Sixty years ago polio was one of the most feared diseases in the developed world. In the early 1950s, 8,000 people were paralysed by polio each year in the UK. Tragically, five to 10 per cent lost their lives after their breathing muscles became immobilised.

Frustrated by the lack of research and treatment centres in the UK Duncan set up the National Fund for Poliomyelitis Research to find a cure for polio. Within 10 years, the first UK polio vaccines were introduced and have kept millions of children safe from this deadly virus ever since.

Research focused on establishing the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines, as well as the right amount to give and the best ways to administer them. They also explored how polio infects humans and how well the vaccines could protect whole populations.

Duncan Guthrie’s own daughter Janet was diagnosed with polio in 1949, at just 20 months old. Her parents were not allowed to see her at all for her first month in hospital and, when visits were eventually allowed, they were limited to once a week - a distressing and painful time for the family and, most of all, for little Janet.

Thankfully, Janet recovered from her illness, but for many thousands that wasn't the case.

Inspired by the desperate need to protect children from polio back in the 1950s, Duncan Guthrie laid the foundations for Action Medical Research. Now, we’re the UK’s leading charity funding vital research to save and change children’s lives and we’re forging ahead to fund research to help better understand the impact of COVID-19 on children.

Sixty years ago polio was one of the most feared diseases in the developed world. In the early 1950s, 8,000 people were paralysed by polio each year in the UK. Tragically, five to 10 per cent lost their lives after their breathing muscles became immobilised.

Frustrated by the lack of research and treatment centres in the UK Duncan set up the National Fund for Poliomyelitis Research to find a cure for polio. Within 10 years, the first UK polio vaccines were introduced and have kept millions of children safe from this deadly virus ever since.

Introducing the first UK polio vaccines

The charity’s early funding helped support polio research across the UK, including the work of Professor George Dick and his team at Queen’s University in Belfast, to test and develop two polio vaccines for use in the UK: the injectable Salk vaccine, first introduced in 1955, and the oral sugar cube Sabin vaccine, introduced in 1962.Research focused on establishing the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines, as well as the right amount to give and the best ways to administer them. They also explored how polio infects humans and how well the vaccines could protect whole populations.

Duncan Guthrie’s own daughter Janet was diagnosed with polio in 1949, at just 20 months old. Her parents were not allowed to see her at all for her first month in hospital and, when visits were eventually allowed, they were limited to once a week - a distressing and painful time for the family and, most of all, for little Janet.

Thankfully, Janet recovered from her illness, but for many thousands that wasn't the case.

Alligatorob

SF VIP

I know several people who had polio, none so bad as to be in the iron lung. As they age however the physical effects on them are getting worse...

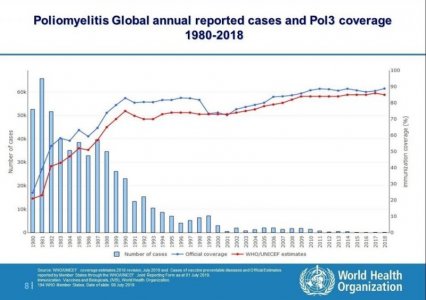

For a long time you could see the scar on my arm from the vaccine, but it has now faded. Polio is a great vaccine success story.

For a long time you could see the scar on my arm from the vaccine, but it has now faded. Polio is a great vaccine success story.

CarolfromTX

Senior Member

- Location

- Central Texas

Polio was a scourge, no doubt. But conflating it with Covid is questionable.

Yes, some use it (along with other diseases) as a pro-vaccine-for-everything argument. Big differences.Polio was a scourge, no doubt. But conflating it with Covid is questionable.

JustinCase

UNIX/Linux

Would rather not respond - delete.

Last edited:

Alligatorob

SF VIP

JaniceM

Well-known Member

- Location

- still lost between two shores..

I was under the impression kids couldn't get into Kindergarten without it- unless there was a legitimate religious exemption; and a couple of years later the "booster" vaccine appeared.. in some locations, on sugar cubes.Strangely, I don't remember if I ever received the polio vaccine or not. I have no memory of it. Maybe it was only given to children?

Remy

Well-known Member

- Location

- California, USA

You should have heard this nut going on about Neil Young on newstalk over the radio. I listen in my car on my lunch break because I prefer it over music and it's about all I can get on the weekends. Even if it's crazy talk IMO. Won't mention names as we're not supposed to get political.I actually saw that both Neil Young and Joanie Mitchell, who withdrew from Spotify due to Joe Rogan's vaccine disinformation, had Polio when they were younger. That is most likely the reason they took such a hard stance against his anti-vaccination stance.

Sassycakes

SF VIP

- Location

- Pennsylvania

A friend of mine's cousin had Polio many many years ago before the vaccine came out. He was in an iron lung for a long time sadly he died at a young age. Fortunately, they invented the Polio Vaccine a few years later. I remember they gave it to us on a cube of sugar. I want to look up and see if anyone got Polio after the vaccine came out.

I totally agree especially when the vaccine for polio KILLED the virus not ......the same at all for Covid " designed to make it mild " and pharmaceutical profits.Polio was a scourge, no doubt. But conflating it with Covid is questionable.

Jeni, let's try some logic. There are three scenarios:

a. A vaccine that 100% kills the virus, no exceptions. Minimal or no side effects.

b. Not having a vaccine, or having one and ignoring it, or preaching against it, resulting in millions of unnecessary deaths. Option b rejects or lies about science, ignites fears and false rumors, and is inextricably linked to a political party and some religions. And trying to justify this irrational fear by throwing in a lot of nonsense about pharmaceutical "profits."

c. Having a vaccine which does not kill 100% of the virus, but kills a lot of it, resulting in, at worst, an unpleasant but mild illness, like a cold or a mild case of flu. No deaths, or hardly any, mainly due to compromised immune systems or other diseases. Most people getting the vaccine never get the illness at all, or at least no symptoms. And continued research, hopefully resulting in option A, before too long.

Of course, I'd choose A if possible. But as a runner-up, I'd definitely go with C.

Which one would you choose?

Your post made me interested enough to do a little research about the original lab that produced the Salk vaccine. Cutter Laboratories was bought by Bayer in 1974. (Uh-oh, big pharma!) Here's what I found in Wikipedia:

In what became known as the Cutter incident, some lots of the Cutter vaccine—despite passing required safety tests—contained live polio virus in what was supposed to be an inactivated-virus vaccine. Cutter withdrew its vaccine from the market on April 27 after vaccine-associated cases were reported.

The mistake produced 120,000 doses of polio vaccine that contained live polio virus. Of children who received the vaccine, 40,000 developed abortive poliomyelitis (a form of the disease that does not involve the central nervous system), 56 developed paralytic poliomyelitis—and of these, five children died from polio.[2] The exposures led to an epidemic of polio in the families and communities of the affected children, resulting in a further 113 people paralyzed and 5 deaths.[3] The director of the microbiology institute lost his job, as did the equivalent of the assistant secretary for health. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Oveta Culp Hobby stepped down. Dr William H. Sebrell Jr, the director of the NIH, resigned.[4]

Surgeon General Scheele sent Drs. William Tripp and Karl Habel from the NIH to inspect Cutter's Berkeley facilities, question workers, and examine records. After a thorough investigation, they found nothing wrong with Cutter's production methods.[5] A congressional hearing in June 1955 concluded that the problem was primarily the lack of scrutiny from the NIH Laboratory of Biologics Control (and its excessive trust in the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis reports).[4]

A number of civil lawsuits were filed against Cutter Laboratories in subsequent years, the first of which was Gottsdanker v. Cutter Laboratories.[6] The jury found Cutter not negligent, but liable for breach of implied warranty, and awarded the plaintiffs monetary damages. This set a precedent for later lawsuits. All five companies that produced the Salk vaccine in 1955—Eli Lilly, Parke-Davis, Wyeth, Pitman-Moore, and Cutter—had difficulty completely inactivating the polio virus. Three companies other than Cutter were sued, but the cases settled out of court.[7]

The Cutter incident was one of the worst pharmaceutical disasters in US history, and exposed several thousand children to live polio virus on vaccination.[3] The NIH Laboratory of Biologics Control, which had certified the Cutter polio vaccine, had received advance warnings of problems: in 1954, staff member Dr. Bernice Eddy had reported to her superiors that some inoculated monkeys had become paralyzed and provided photographs. William Sebrell, the director of NIH, rejected the report.[

a. A vaccine that 100% kills the virus, no exceptions. Minimal or no side effects.

b. Not having a vaccine, or having one and ignoring it, or preaching against it, resulting in millions of unnecessary deaths. Option b rejects or lies about science, ignites fears and false rumors, and is inextricably linked to a political party and some religions. And trying to justify this irrational fear by throwing in a lot of nonsense about pharmaceutical "profits."

c. Having a vaccine which does not kill 100% of the virus, but kills a lot of it, resulting in, at worst, an unpleasant but mild illness, like a cold or a mild case of flu. No deaths, or hardly any, mainly due to compromised immune systems or other diseases. Most people getting the vaccine never get the illness at all, or at least no symptoms. And continued research, hopefully resulting in option A, before too long.

Of course, I'd choose A if possible. But as a runner-up, I'd definitely go with C.

Which one would you choose?

Your post made me interested enough to do a little research about the original lab that produced the Salk vaccine. Cutter Laboratories was bought by Bayer in 1974. (Uh-oh, big pharma!) Here's what I found in Wikipedia:

Cutter incident

On April 12, 1955, following the announcement of the success of the polio vaccine trial, Cutter Laboratories became one of several companies that was recommended to be given a license by the United States government to produce Salk's polio vaccine. In anticipation of the demand for vaccine, the companies had already produced stocks of the vaccine and these were issued once the licenses were signed.In what became known as the Cutter incident, some lots of the Cutter vaccine—despite passing required safety tests—contained live polio virus in what was supposed to be an inactivated-virus vaccine. Cutter withdrew its vaccine from the market on April 27 after vaccine-associated cases were reported.

The mistake produced 120,000 doses of polio vaccine that contained live polio virus. Of children who received the vaccine, 40,000 developed abortive poliomyelitis (a form of the disease that does not involve the central nervous system), 56 developed paralytic poliomyelitis—and of these, five children died from polio.[2] The exposures led to an epidemic of polio in the families and communities of the affected children, resulting in a further 113 people paralyzed and 5 deaths.[3] The director of the microbiology institute lost his job, as did the equivalent of the assistant secretary for health. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Oveta Culp Hobby stepped down. Dr William H. Sebrell Jr, the director of the NIH, resigned.[4]

Surgeon General Scheele sent Drs. William Tripp and Karl Habel from the NIH to inspect Cutter's Berkeley facilities, question workers, and examine records. After a thorough investigation, they found nothing wrong with Cutter's production methods.[5] A congressional hearing in June 1955 concluded that the problem was primarily the lack of scrutiny from the NIH Laboratory of Biologics Control (and its excessive trust in the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis reports).[4]

A number of civil lawsuits were filed against Cutter Laboratories in subsequent years, the first of which was Gottsdanker v. Cutter Laboratories.[6] The jury found Cutter not negligent, but liable for breach of implied warranty, and awarded the plaintiffs monetary damages. This set a precedent for later lawsuits. All five companies that produced the Salk vaccine in 1955—Eli Lilly, Parke-Davis, Wyeth, Pitman-Moore, and Cutter—had difficulty completely inactivating the polio virus. Three companies other than Cutter were sued, but the cases settled out of court.[7]

The Cutter incident was one of the worst pharmaceutical disasters in US history, and exposed several thousand children to live polio virus on vaccination.[3] The NIH Laboratory of Biologics Control, which had certified the Cutter polio vaccine, had received advance warnings of problems: in 1954, staff member Dr. Bernice Eddy had reported to her superiors that some inoculated monkeys had become paralyzed and provided photographs. William Sebrell, the director of NIH, rejected the report.[

Lewkat

Senior Member

- Location

- New Jersey, USA

There is an excellent book by Debbie Bookchin and Jim Schumacher titled, The Virus and the Vaccine which covers the contaminated Salk Vaccine from the 1950s through 1961 and the horrifying results of that. I read the book some time ago and still have it in my library. Salk's vaccine contained contaminated elements from monkey's kidney's. It explains how all this happened and it is an eye opener for certain.

mellowyellow

Well-known Member

The first Salk vaccines were distributed across Australia in June 1956. I was standing in a long line in the school playground, under a blazing sun, waiting for the jab. Duncan Guthrie is an unsung hero.

DUNCAN GUTHRIE was a nonparty socialist concerned with the health and welfare of children throughout the world.

.............When Director of the NFPR, he had to be persuaded to accept an increase in salary for himself. Their first headquarters was two tiny dark rooms up three flights of stairs above a fruit shop in Spenser Street, in Westminster. He deplored the development of palatial offices and large staffs by charities and insisted that money collected for a charity should be spent on its aims………..

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-duncan-guthrie-1444138.html

DUNCAN GUTHRIE was a nonparty socialist concerned with the health and welfare of children throughout the world.

.............When Director of the NFPR, he had to be persuaded to accept an increase in salary for himself. Their first headquarters was two tiny dark rooms up three flights of stairs above a fruit shop in Spenser Street, in Westminster. He deplored the development of palatial offices and large staffs by charities and insisted that money collected for a charity should be spent on its aims………..

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-duncan-guthrie-1444138.html